Introduction

John Clarke, former major organizer for the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP), recently posted on Facebook the following:

When state enforcers kick in your door and take you away, in order to suppress the ideas you are promoting, this is most certainly an act of very direct censorship.

When wealthy interests dominate the means of disseminating views and information and block the ability of dissenting perspectives to reach a wide audience, you can make a strong case for this being a form of censorship.

When, however, someone removes your comment from their personal Facebook page because they consider it unhelpful or inappropriate, they are only ensuring that their page, which isn’t the public square, is being used in the way they have decided it should be. The removal of your comment may annoy you and you are free to unfriend the person but you are not the victim of censorship.

I thoroughly disagree with this argument. Clarke’s only basis for claiming that ‘removing a comment from one’s personal Facebook page’ is not censorship is because it is the person’s “personal Facebook page.” This may apply if the content of what is posted on a person’s Facebook page is personal. However, the majority of the content of Clarke’s posts are political in one way or another. As political, they are public, and as public, they should be subject to challenging such views.

Private Property, Free Speech and Censorship

It is interesting that Clarke seems to use the idea that a person’s Facebook page is “personal” in the sense of his or her absolute private property in order to justify removal of comments. Could not employers use a similar argument to justify suppressing any dissent at work? Do not employers use their power over “their property” to stifle workers’ expression of their beliefs? This situation is less so in the public sector than in the private sector. From Bruce Barry (June 2006), “The Cringing and The Craven: Freedom of Expression In, Around, and Beyond the Workplace,” Business Ethics Quarterly,page 9:

(in the U.S.) “particularly in the private sector, employers enjoy nearly untrammeled

power to censor and punish the speech of their employees” (Estlund 1997: 689). Public sector employees in many countries (including the U.S.) have non-trivial free speech rights by law, and in some places and under some conditions these rights can extend to the private sector.

However, through control over property the power of employers to hire and fire workers in both sectors, in addition to engaging in such acts as performance appraisals, often limits such expression. page 8:

Second, the workplace itself is changing in ways that render rights to expression both

more threatened and more important. Yamada (1998) developed this argument, describing several factors that raise concerns about employers’ inclination to limit workplace expression: individual economic insecurity that breeds self-censorship at work, a rise in electronic surveillance of workers, a decline in unionization, an expansion in corporate political partisanship (which ostensibly chills employee expression that might deviate from the preferred point of view), and the simple fact that people work longer hours than in the past.

Clarke’s attempt to justify his acts of removal of comments from “his” Facebook page are just as lame as employers’ and their ideologues’ attempts to justify their acts of censorship against workers. Page 40:

To say that the existing landscape for workplace expression does not accord with lofty theoretical views of the functions of free speech is more than just a rhetorical flourish; it sounds an alarm about the civic health of a society that treats free expression as a foundational value, yet gives employers imperious power to limit speech – both at and after work – in ways that an autocrat might admire.

Conclusion

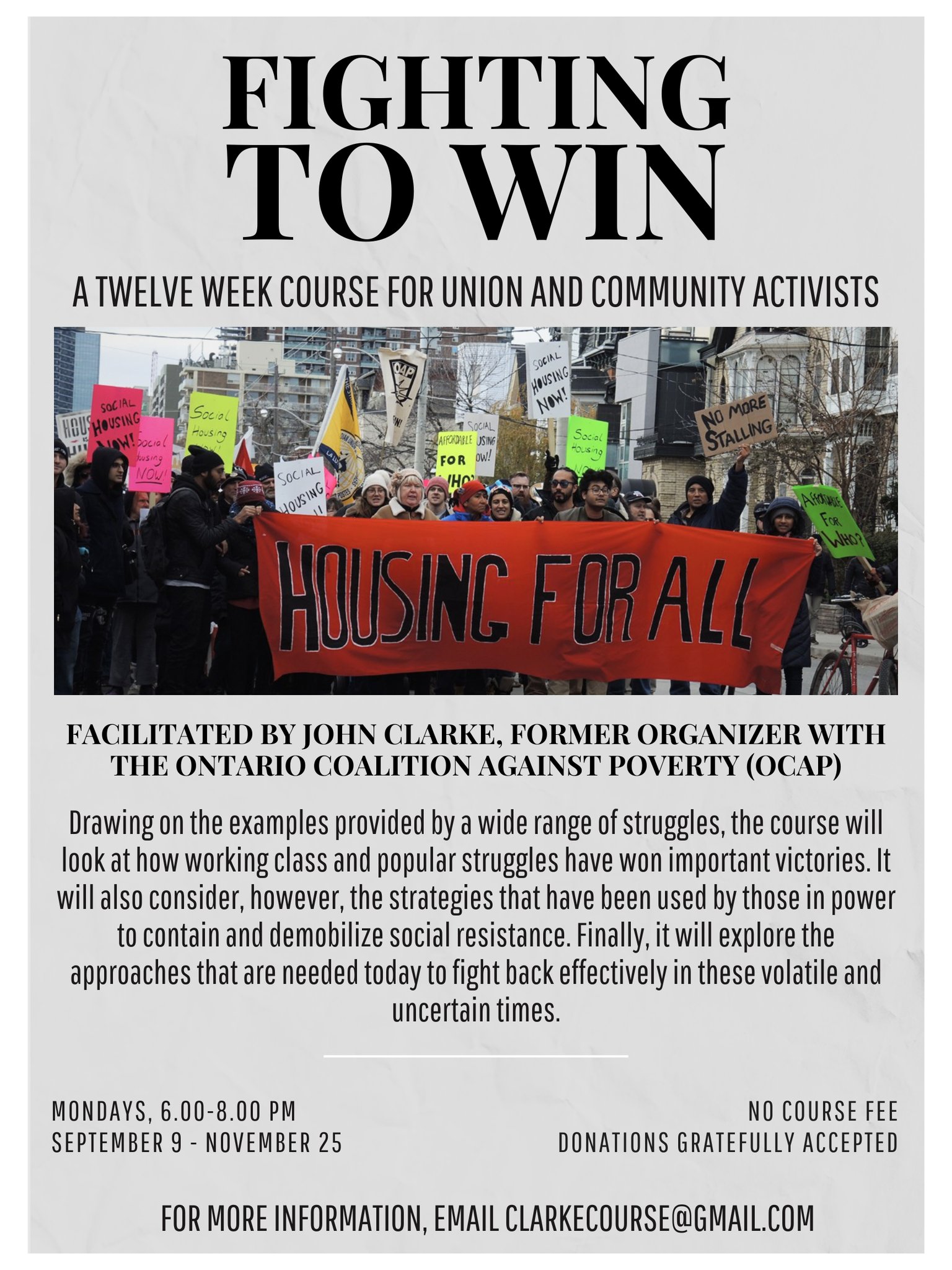

Clarke’s implicit justification for deleting comments from his Facebook page is similar to the power of employers to limit comments made by workers: employers’ own the buildings, machines (including computers), etc., and this ownership, along with the wage they pay the workers, gives them the right to limit what workers say or write. Clarke, similarly, treats his Facebook page as his private property–despite its explicit political content, and justifies his deletion of comments on the basis that it is his personal Facebook page. This parallel is not a good sign, given that Clarke will be giving a course soon on how to fight to win for community and union activists: